Bush Vows to Keep Spying On You For Your Own Good

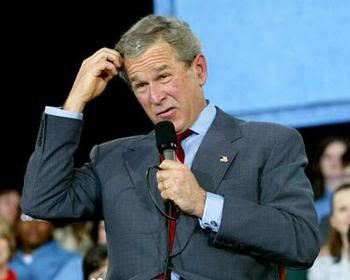

WASHINGTON -- In a news conference today President Bush made a strident defense of the use of domestic spying without court orders.

"What some people don't seem to understand is that we are at war here, and that my being able to spy on you without any oversight is a vital tool in this war," said the President.

"I swore an oath to uphold the laws and to defend the Constitution, and I will do that, even if it requires that I abridge your fundamental civil rights."

When a reporter pointed out that there seemed to be a contradiction in preserving our rights by violating our rights, the President became visibly irritated.

"Look," said an exasperated President Bush, "in order to preserve our democracy, I have to have the absolute power to do whatever I decide is necessary. Are we clear? I said, are we clear??"

The President then motioned to his Chief of Staff, Andrew Card, and had the reporter dragged from the room.

"Sometimes you have to kill the patient in order to save the patient."

"What some people don't seem to understand is that we are at war here, and that my being able to spy on you without any oversight is a vital tool in this war," said the President.

"I swore an oath to uphold the laws and to defend the Constitution, and I will do that, even if it requires that I abridge your fundamental civil rights."

When a reporter pointed out that there seemed to be a contradiction in preserving our rights by violating our rights, the President became visibly irritated.

"Look," said an exasperated President Bush, "in order to preserve our democracy, I have to have the absolute power to do whatever I decide is necessary. Are we clear? I said, are we clear??"

The President then motioned to his Chief of Staff, Andrew Card, and had the reporter dragged from the room.

"Sometimes you have to kill the patient in order to save the patient."

3 Comments:

December 20, 2005

NSA and Bush's Illegal Eavesdropping

When President Bush directed the National Security Agency to secretly eavesdrop on American citizens, he transferred an authority previously under the purview of the Justice Department to the Defense Department and bypassed the very laws put in place to protect Americans against widespread government eavesdropping. The reason may have been to tap the NSA's capability for data-mining and widespread surveillance.

Illegal wiretapping of Americans is nothing new. In the 1950s and '60s, in a program called "Project Shamrock," the NSA intercepted every single telegram coming into or going out of the United States. It conducted eavesdropping without a warrant on behalf of the CIA and other agencies. Much of this became public during the 1975 Church Committee hearings and resulted in the now famous Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) of 1978.

The purpose of this law was to protect the American people by regulating government eavesdropping. Like many laws limiting the power of government, it relies on checks and balances: one branch of the government watching the other. The law established a secret court, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC), and empowered it to approve national-security-related eavesdropping warrants. The Justice Department can request FISA warrants to monitor foreign communications as well as communications by American citizens, provided that they meet certain minimal criteria.

The FISC issued about 500 FISA warrants per year from 1979 through 1995, and has slowly increased subsequently -- 1,758 were issued in 2004. The process is designed for speed and even has provisions where the Justice Department can wiretap first and ask for permission later. In all that time, only four warrant requests were ever rejected: all in 2003. (We don't know any details, of course, as the court proceedings are secret.)

--Bruce Schneier is an internationally renowned security technologist and author. Described by The Economist as a "security guru," Schneier is best known as a refreshingly candid and lucid security critic and commentator.

Bush is defiantly battling critics, insisting that his decision to conduct warrantless wiretaps on hundreds of people inside the United States, including American citizens, was necessary and fully consistent with the Constitution and federal law. Neither claim stands up to scrutiny. The president acted unnecessarily and, more significantly, in direct violation of a criminal law.

The secret spying program was said to be necessary because getting court approval under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act is too time-consuming. That position is difficult to accept: Warrants requested under FISA can be approved in a matter of hours, and the statute allows the government in emergency situations to put a wiretap in place immediately and then seek court approval later, within 72 hours. But the true reason behind the administration's position is less difficult to decode -- the desire to circumvent a key limitation of FISA. Despite the statute's breadth, it permits wiretaps only on agents of foreign powers, and would not have permitted them on persons not directly connected to al-Qaida. Apparently seeking to cast a much wider net after 9/11, the president simply ignored the law and unilaterally -- and secretly -- authorized warrantless wiretaps on Americans.

Was it legal to do so? Attorney General Alberto Gonzales argues that the president's authority rests on two foundations: Congress' authorization of the president to use military force against al-Qaida and the Constitution's vesting of power in the president as commander in chief, which necessarily includes gathering "signals intelligence" on the enemy. But that argument cannot be squared with Supreme Court precedent. In 1952, the Supreme Court considered a remarkably similar argument during the Korean War. Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, widely considered the most important separation-of-powers case ever decided by the court, flatly rejected the president's assertion of unilateral domestic authority during wartime. President Truman had invoked the commander-in-chief clause to justify seizing most of the nation's steel mills. A nationwide strike threatened to undermine the war, Truman contended, because the mills were critical to manufacturing munitions.

*

Like Truman, President Bush acted in the face of contrary congressional authority. In FISA, Congress expressly addressed the subject of warrantless wiretaps during wartime, and limited them to the first 15 days after war is declared. Congress then went further and made it a crime, punishable by up to five years in jail, to conduct a wiretap without statutory authorization.

*

It is possible, of course, that the president's advisors overlooked the Youngstown precedent, despite its status as the court's most important case on executive power during wartime. In the infamous Justice Department torture memorandum of August 2002, John Yoo -- who also reportedly wrote the memo justifying domestic wiretaps -- made a similar argument that the commander-in-chief authority included the power to order torture, in direct contravention of a statute criminalizing torture and a treaty prohibiting it under all circumstances. That memo did not even cite Youngstown. But ignorance is no excuse. The president acted in clear contravention of a criminal law enacted by Congress and a Supreme Court precedent, both directly on point.

Bush acted, in other words, as if there are no checks and balances in the American system of government. Some things changed drastically after 9/11, but we cannot allow that to be one of them.

--David Cole is a law professor at Georgetown University and author of "Enemy Aliens: Double Standards and Constitutional Freedoms in the War on Terrorism" (New Press, 2003). http://www.salon.com/opinion/feature/2005/12/20/spying/

i don't care if bush wants to listen to my phone calls, emails, etc. if you've got nothing to hide you won't care either.

Post a Comment

<< Home